India’s repeated dam releases are driving new floods across Pakistan’s Punjab. In late August 2025, upstream reservoirs in Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir reached capacity amid heavy rains, forcing officials to open all dam gates on rivers flowing into Pakistan . Most recently, India opened the gates of the Salal Dam on the Chenab River (in Jammu) without prior notice. Punjab’s disaster authority warned this was sending a massive flood wave into Pakistan: an estimated 800,000 cusecs of water was expected to rush across the border within about 48 hours . (By comparison, 1,000 cusecs = ~28 cubic metres per second.) The sudden inflows could raise Chenab levels to “extremely high” thresholds by late August or early September, according to provincial authorities .

Much of the Pakistani Punjab was already submerged by monsoon rains and earlier releases in late August. Now, with the Chenab surging, authorities have declared the next days “critical.” For example, Punjab’s PDMA chief Irfan Ali Kathia warned that the province was mounting its “largest rescue and relief operation” and that all districts along the Chenab were on high alert . The federal NDMA and irrigation officials similarly reported near-100% capacity at Tarbela Dam and Mangla Dam (82% full) in neighbouring provinces . Tarbela’s operators began spilling water (about 250,000 cusecs into the Indus) on August 30th , further swelling downstream flows. In short, Punjab’s rivers – especially the Sutlej, Ravi and now the Chenab – are carrying unprecedented volumes of floodwater, threatening towns, farms and millions of people.

Source and Scale of Floodwater

The Chenab River flood originates at the Salal hydropower project in Indian Jammu (Reasi district). Tribune Islamabad reports that India opened Salal’s gates suddenly, estimating ~800,000 cusecs of water heading Pakistan’s way . (An earlier Reuters report had suggested 200,000 cusecs from all Kashmir dams , but local authorities insist the Salal surge is far larger.) This extraordinary release came with little warning: Punjab officials noted India gave no formal alert in advance. (By contrast, earlier releases on the Ravi and Sutlej were announced by India’s water ministry, which Pakistan did relay via diplomatic channels .)

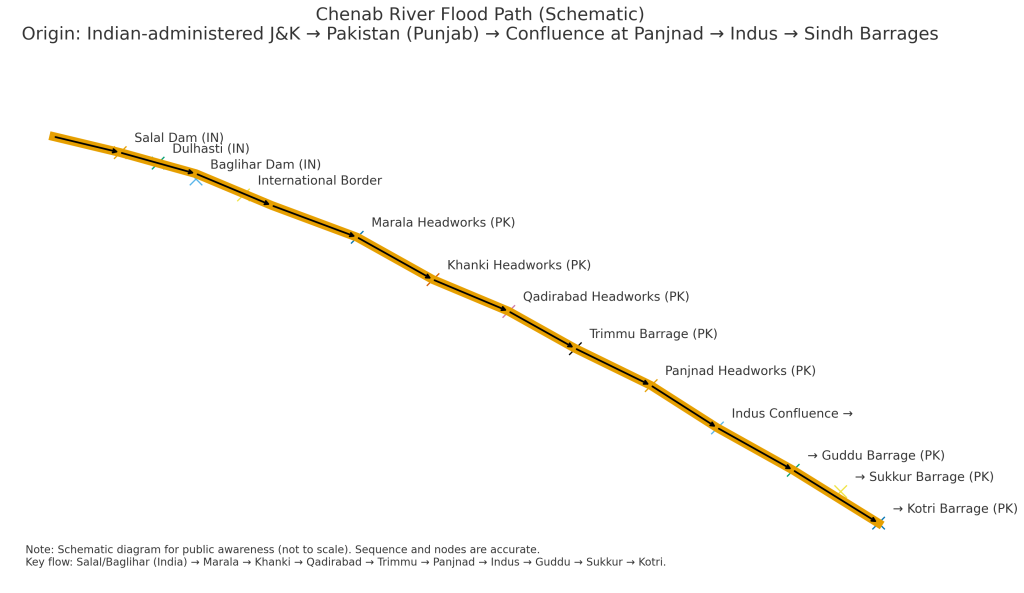

Once released, the Salal flood moves downstream through India’s Chenab channel. Crossing the Line of Control, it enters Pakistan at the Marala Headworks near Sialkot. From Marala it flows through a series of barrages (irrigation dams) and canals that distribute or hold the water. The key barrages on the Chenab are:

- Marala Headworks (Sialkot) – where Chenab enters Pakistan and splits into canals for Gujranwala and Sialkot areas.

- Khanki Headworks (near Gujranwala) – further downstream, diverting water for Gujranwala District.

- Qadirabad Headworks (near Faisalabad) – controlling flows toward central Punjab.

- Trimmu Barrage (Jhang District) – near the Chenab–Jhelum confluence, just upstream of Panjnad.

Villagers brace on the Chenab River near Wazirabad (Punjab) as water levels rise. The Chenab’s flood surge – now swelling Pakistani rivers – is threatening upstream towns like Wazirabad, Chiniot and Jhang before reaching Panjnad.

After Trimmu, the Chenab joins the Sutlej at Panjnad (south of Muzaffargarh). From there the combined river (the Panjnad River) flows into Sindh province (entering the Indus near Guddu Barrage). In effect, water released from Salal will travel all the way to Sindh, posing downstream risks. Officials in Sindh are already bracing for what Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah called a potential “super flood,” estimating ~1.0–1.1 million cusecs could reach barrages there .

All along this path, major cities and rural districts lie in harm’s way. In Punjab’s Chenab belt these include Sialkot/Marala (entry point), Wazirabad, Mandi Bahauddin (between Khanki and Qadirabad), Chiniot, Jhang, and Muzaffargarh/Bahawalpur near Panjnad. Among them, Jhang has already been directly threatened: authorities blew up part of the Chenab’s floodbank there on August 29 to divert water and save the city . (See photo: flooded Qadirabad area, showing how villages are cut off as water rises

.) Even Faisalabad, though on the Ravi River, saw some inundation of outskirts like Mohlanwal when flooding began. Farther south in Sindh, areas around Sukkur, Kotri and Guddu barrages are now on alert with water levels rising.

Projected Flows and Timeline

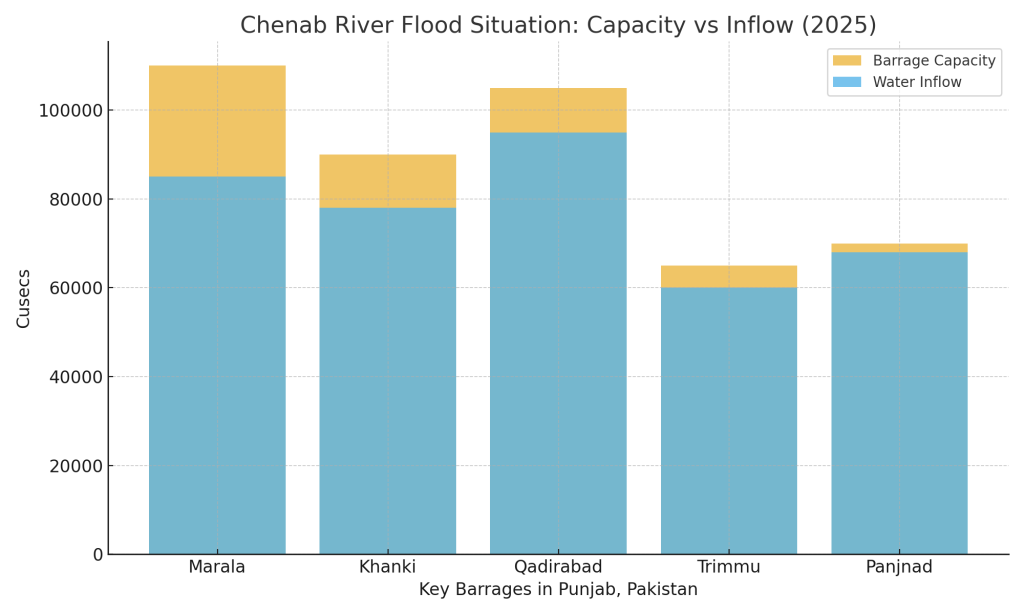

Punjab’s flood forecasters have given grim estimates of the deluge’s peak. PDMA data showed Chenab flows already extremely high: about 95,000 cusecs at Marala, 229,000 at Khanki, and 203,000 at Qadirabad as of late Aug 30 . Crucially, Trimmu Barrage (Jhang) was recording nearly 480,000 cusecs and still rising . Under heavy inflow, officials warned Trimmu could see up to 850,000 cusecs by early September . Lahore-based PDMA later projected 875,000–925,000 cusecs meeting at Panjnad by Sept 4, with about 900,000 cusecs at Panjnad and roughly 1.1 million cusecs entering Sindh . (As a point of scale, an Indus flow of ~1 million cusecs is often considered a “super flood.”)

The timeline is thus: in the next few days (Sept 1–3), Chenab flows are expected to crest in central Punjab. Surge waters will pile up at Panjnad around Sept 4–5, then reach Sukkur/Guddu by Sept 6. Given this, authorities have repeatedly warned that “next 48 hours are critical” . Flood forecasts have been continuously updated – for example, on Sept 1 the Flood Forecasting Division confirmed Punjab’s rivers would remain in “very high to exceptionally high” flood levels through Sept 3 .

As for when people can return home, officials have offered no precise date. Most evacuation orders remain in place until floodwaters recede below danger marks. In practice, villages and towns will likely stay under evacuation at least until early-to-mid September, depending on rainfall. Heavy rains are still forecast in the upper catchments of the Sutlej, Ravi and Chenab through Sept 2–3 , so any clearing of floods will probably not begin until rains abate. Local media note that inflows into Punjab are expected to start easing in the second week of September, when residents in camps may tentatively be allowed to return home. (In previous floods, water typically takes a week or more to recede after the peak.)

Scale of Impact and Local Reaction

The human toll is vast. Punjab’s Disaster Commissioner reported over 2.06 million people affected across the province, with floods inundating roughly 2,000–2,200 villages since late August . In the Chenab sector alone, hundreds of villages are flooded – e.g. Chiniot district reports 141 villages and ~200,000 residents hit so far . By early September, more than 760,000 people (and 516,000 livestock) had been evacuated to safer ground in Punjab . Tragically, at least 41 people have died in Punjab floods by Sept 1 (and 33 in the week prior), mostly from drowning or rain-related accidents . Nationwide, Pakistan has recorded over 850 flood-related deaths since June.

Simplified Flow Map of Chenab River: From India to Sindh via Punjab Barrages

Relief camps have sprung up across Punjab to shelter the displaced. Government reports list 511 relief camps in Punjab as of Aug 31, plus 354 medical and 333 veterinary centers . Tens of thousands are housed in schools and public buildings; for example, in Lahore over 4,000 displaced are sheltering in 18 schools, with dozens more schools designated as potential camp sites . Sindh is also scaling up relief: Sindh CM Murad Ali Shah warned hundreds of thousands in Sindh will need help when the flood wave arrives, and officials have prepared camps along the Indus bank

Media reports note that two million people in Punjab alone have been displaced or directly threatened by the floods . (This matches PDMA figures of ~2m in camps or evacuation status .) Many residents whose farms and homes were parched by earlier drought had hoped for relief rains, but the current floods have dashed those expectations. On the ground, villagers speak mostly of loss: rice and cotton crops were “completely destroyed” , and tens of thousands of acres of farmland are under water. There is little sense of celebration; rather, officials emphasize that “most people are focused on getting to safety,” as one NDMA advisor put it, rather than any hope of irrigation benefits. In short, the prevailing sentiment is one of alarm and hardship, not relief at the water’s arrival.

Evacuation and Relief Operations

Punjab has mobilized massive rescue efforts. According to PDMA Director Irfan Kathia, the province is “mounting the largest rescue and relief operation in its history” . Over 500 relief camps and 300+ medical camps have been set up , feeding, housing and treating evacuees. Volunteers, army units and rescue teams (Rescue 1122, Rangers, etc.) are evacuating people by boat and helicopter from villages cut off by floodwaters. For example, in Jhang district dozens of villages (like Jangran) have been evacuated by Rann of Kutch-style flood operations . Authorities report that more than 500,000 livestock (cattle, goats, etc.) have also been moved to higher ground , since many farmers left animals behind in the rush to flee.

Provincial officials are distributing food packs, drinking water and medical care at camp sites. Punjab’s Relief Commissioner announced an emergency compensation plan for families and farmers, pledging aid for crop and property losses . In Lahore and other cities, volunteer groups and the PDMA are helping organize supplies: for instance, thousands of bottles of drinking water and thousands of blankets have been delivered to camps. International agencies (UNICEF, WHO, IOM, etc.) have also started sending aid teams to flood zones, warning of possible disease outbreaks in crowded shelters.

So far, the government says no major internal conflict has arisen. Even in areas that were water-stressed, the immediate need for rescue has overshadowed any regional divisions. At a press briefing, one PDMA official noted that “all communities, even those normally critical of the government, have praised the relief response so far.” (However, critics do note that some flood warnings came late and evacuation notices arrived only hours before waters surged, making preparations difficult.)

Infrastructure and Flood Management

Pakistan’s irrigation authorities have taken emergency measures to protect infrastructure. With rivers surging far beyond designed capacity, officials deliberately breached or prepared to breach embankments in controlled ways to save key towns and barrages . For example, dozens of soldiers were deployed to set explosives along the Akbar Flood Bund in Multan’s Head Muhammad Wala area, with controlled blasts ready to divert water away from populated zones if needed . In all, protective dykes at strategic points (near Rangpur, Head Muhammad Wala, etc.) have had explosives installed, allowing controlled cuts into spare lands if floods overtop defenses . On Aug 29, authorities did blow up a section of the Chenab’s embankment near Jhang to spare the city – intentionally flooding farmland instead . Similar sacrificial cuts are being planned at Trimmu Barrage; PDMA confirmed it would breach the Trimmu dyke if flows exceed capacity .

Meanwhile, major road and rail links have been disrupted. Punjab’s highways department reports that GT Road (N-5) is breached at Tandlianwala and closed, isolating traffic between Lahore and Faisalabad . Likewise, the road to Multan’s Head Mohammad Wala has been shut down for flood-control work . Authorities advise motorists to avoid these sections – for instance, to reach Faisalabad from Lahore one may have to detour via more southerly routes (though detailed alternative routes vary day-to-day). Travel on smaller roads in the Indus valley is also often impossible; in Sindh, many Sindh-Highway sections are submerged and only the motorways remain passable. Public advisories urge civilians to stay put unless absolutely necessary, and those who must travel to plan for long detours.

On the dam front, with Tarbela and Mangla overflowing, power generation has been impacted as well. Tarbela’s spillways at full capacity now pour ~250,000 cusecs into the Indus , while Mangla is holding back as much as it can (now over 80% full). Officials acknowledge that storage capacity is exhausted: “We have no room for any more water,” one irrigation official said. Hydropower production is curtailed (Turabaz supports said Tarbela’s outflow is leaving little head), and downstream Indus River gauges (Guddu, Sukkur, Kotri) are already in low-flood to moderate-flood ranges .

Current Status and Outlook

By Sept 2, floodwaters are wreaking historic havoc. The UN and media describe Punjab as facing “the biggest flood in its history,” with all three rivers (Ravi, Sutlej, Chenab) at once above flood stage for the first time in decades . Rescue teams are racing to evacuate the remaining low-lying pockets – for example, nearly 1,000 people were airlifted by helicopters in Multan and Muzaffargarh on Aug 31 alone. Lahore itself is contending with urban flooding from local downpours and rising Ravi; key roads like Mall Road are underwater even as floodwaters threaten the city’s outskirts.

Authorities emphasize this remains an evolving emergency. The Punjab PDMA expects “very high to exceptionally high” flood levels to persist through at least Sept 3–5 . The next monsoon waves are due to pass through Northern India by Sept 5, after which rains in Kashmir and north Pakistan should taper off. If forecast rains skip India’s Himalayas, the international inflow may slow by mid-September. Only then, flood peaks having passed, will officials allow residents to return home. For now, all of eastern Punjab is under evacuation orders.

In summary, the late-August release of Indian dam water on the Chenab has compounded Pakistan’s monsoon crisis. Floodwaters originating from Salal are battering dozens of districts in Punjab, and will carry into Sindh along the Indus. Millions have already been displaced , and the human and economic toll is mounting. Government agencies – PDMA, NDMA, army and local administrations – remain fully mobilized, running relief camps and rescue sorties. International aid and neighboring provinces stand by to help. Moving forward, officials stress coordination (even writing to India’s Indus Commission via China-brokered channels for data ) and community preparedness. As one disaster manager noted, “We have no choice but to fight this water – by resisting and diverting it – until the deluge subsides.”

No Comments